The

Morgan Effigy

The

Morgan Effigyby Gary E. Theall

Long before the Cajuns, Robert Perry, the Americans, or any other Europeans occupied the territory now known as Vermilion Parish, several groups of Native Americans used it as their hunting and ceremonial grounds. Evidence of their occupation was found by the early settlers and also by later occupants, in the form of arrowheads, pottery shards, and other ancient artifacts. An area particularly rich in these artifacts was Pecan Island, where several mounds of different sizes could also be found.

In the Spring of 1926, Henry B. Collins, Jr., assistant entomologist at the Smithsonian Institution, conducted a survey of the Native American mounds in southwest Louisiana and the Gulf Coast—the first such survey for the mounds at Pecan Island. The Abbeville Meridional reported on his work at Pecan Island by printing a letter that Collins wrote back to P. O. Broussard, local postmaster, after concluding his investigations:

Abbeville Meridional 6-19-1926:

Smithsonian Institution

United States National Museum

Washington, D. C.

New Orleans, La.,

June 17, 1926.

Mr. P. O. Broussard,

Abbeville, La.

Dear Mr. Broussard:

Somewhat late I carry out my promise to write you something concerning my trip to Pecan Island and the very interesting things I found there.

As you know, the whole Gulf region from Vermilion Bay to Galveston Bay was formerly the territory of the Attakapas Indians, one of the least advanced of the tribes of North America. These people were cannibals, did not have permanent settlements such as many other southern tribes had, and on the whole possessed a very low culture. Pecan Island being in this region, I naturally supposed that whatever Indian remains would be found would have been left by the Attakapas. Instead of this, however, I found evidences of a high cutlure [sic], or perhaps I should say two cultures. Pecan Island, as you are well aware is an old beach, and represents a former position of the Gulf, being built up of crushed shell and soil. This material had been utilized by the Indians in building their mounds, twenty-two of which are on the Island. These mounds are in three or perhaps four groups; first those on Cypress point, next, the Veazey mounds, then the Morgan mounds. I am not certain whether the three smaller mounds, to the east of the Morgan group belong with that group, but I am inclined to believe that they do not. These distinctions are worth noting because the evidence as viewed at the present time seems to indicate that there were two distinct cultures represented on Pecan Island, the four large mounds on Mr. Morgan's place being one, and the Veazey and other scattered mounds belonging to the second group. Unfortunately, the largest mound on the Morgan place has suffered to an unusual degree from the activities of "money-hunters," and its value from a scientific standpoint has been greatly impaired. However I was able to do enough digging to observe the stratification and to get a dozen or more skulls from near the top. All of the Morgan mounds are stratified, that is the material from which they were constructed—mostly crushed shell,—was not piled up at one time, but was deposited in layers, each layer representing a certain period of time, the people having lived successfully [sic, successively?] on one level after another. The skulls from these four mounds all showed artificial head deformations, which resulted from the curious custom of these Indians of binding the heads of their infants to the cradle and applying a steady pressure by means of a flat board to the forehead. This left the forehead perfectly flat, and no doubt was quite painful to the child. The custom is found among many North American tribes, principally in the Southern States and along the North West Coast. The pottery from these four mounds is of the finest type that I have yet seen in Louisiana; indeed it can safely be said that in symmetry of form and beauty of finish, the vessels of these Pecan Islanders was surpassed by no other Indians North of Mexico, save perhaps the ancient Pueblo and Cliff Dwellers of the arid Southwest. I have found similar pottery, though not usually so finely made, all along the Gulf Coast of Louisiana. The material found with the burials in the Morgan mounds was very limited. Apparently it was not the custom of these people to include offerings, with their dead. So much for the Morgan mounds. On the Veazey place and on the Capell place I explored burial grounds which showed somewhat different conditions from those just described. Altho[ugh] the Capell burial ground is some distance off from the Veazey mounds there can be no doubt but that the culture represented is the same, for the type of skulls found, and the objects accompanying the burials were almost identical. To briefly summarize, these sites yielded skulls which were undeformed, pottery which was fairly good but which falls short of the Morgan type; shell beads; bone awls; animal bones; stone and bone weapons and ornaments; sheet-copper ornaments. I showed you most of this material so I need not describe it. It should be said, however, that the ornaments of sheet copper are of considerable importance in placing the culture of these people, for the objects are of a type rather commonly found in the older mounds of the Mississippi and Ohio Valleys and the Gulf States. The copper was obtained probably in trade from the mines of the Lake Superior region. It is particularly fortunate that the skulls from these two sites are undeformed, for when skulls have been artificially flattened they are not of much value to the anthropologist as it is practically impossible to tell what was the original shape. This series of fifty some odd skulls, all undeformed, will therefore give us a fairly good idea as to the physical type of these people, and it will be about the first knowledge that we have of them in this connection, since there is no skeleton material in any of the large museums from this particular region. To sum up the rather disconnected account we can say that the material obtained was left by some unknown tribes, but certainly not the Attakapas and certainly much earlier than the Attakapas. It is of course impossible to say who these people were, but it seems reasonable to suppose that they were the ancestors of some of our Southern tribes—the higher ones—and perhaps the Chitimache, to be more specific. The evidence here is purely circumstantial.

I wish that you could have come to Pecan Island a week earlier and been with us as we dug up these things. One cannot get the same impressions when seeing them bundled together in a bag as when they are in their natural setting. Please allow me to assure you of my appreciation of the interest you have shown in the work. It has been a real pleasure to have known you and I hope that later I may be able to do some further work in your part of the country and see you again.

Very sincerely yours,

Henry B Collins, Jr.

(Columbia, Miss.)

Collins noted that the four Morgan mounds, which revealed evidence of a higher culture than did the other mounds on Pecan Island, were in the form of a square surrounding a central plaza area, suggesting that the mounds may have been used for ceremonial purposes.

The Morgan site was further mapped by the Lower Mississippi Survey in 1979. Dr. Ian Brown and Richard S. Fuller, Jr., conducted the survey. They concluded that the Morgan site was one of the most important mound sites along the southwest Louisiana coast. The mounds were occupied by one or more groups of Native Americans during what is known as the Coles Creek period, about AD 700 to 1000. Mound 4, which was more or less intact when Collins had made his investigation, had been destroyed in the 1950s for the laying of a highway. During the course of the 1979 survey of the remaining three mounds, Dr. Brown met Norman Vaughn, current owner of the Morgan site, who was planning to build a home on the property. Dr. Brown tried to discourage Vaughn from altering the site to any great extent, as the site should be preserved for a future state park.

As fate would have it, financial reverses attributable to the downturn in the oil industry in Louisiana in 1986 caused Vaughn to sell Mound 2 for fill dirt. One of the purchasers, Bert Broussard, as he was spreading some of the dirt from the mound, found a carved deer antler embedded in it. The carving was brought to the attention of archaeologists, who examined it and pronounced it to be a genuine work of art from the Coles Creek period; in fact, the only non-ceramic work of art from that period. The artifact was given the name, "Morgan Effigy." The news of the discovery of the Morgan Effigy created quite a stir in the archaeological community, and generated renewed interest in the excavation of Native American mounds.

Vaughn then announced his intention of dismantling Mound 1 to sell the dirt. Gerard Sellers, a local historian, upon learning of this plan, contacted Dr. Brown, who immediately sent out an alert to several granting agencies and to others. The matter came to the attention of Una B. Evans, one of the directors of the Vermilion Historical Society, who notified the president, Gary E. Theall. An emergency meeting of the VHS board was called to plan a course of action.

Theall began to negotiate with Vaughn. Theall tried to negotiate for the preservation of the mound, but Vaughn was determined to remove it from his property. Further negotiations resulted in a contract giving the VHS the right to have Mound 1 professionally excavated, with VHS receiving the ownership of any artifacts found, and Vaughn retaining the ownership of the dirt. The contract required VHS to raise $15,000.00 in a short time. The matter was publicized, donations began to come in, and through the beneficence of a wealthy Abbeville family and their company, under condition of anonymity, the raising of the required funds was guaranteed.

In the meantime, Una B. Evans personally purchased the Morgan Effigy from Bert Broussard, and executed an act of donation transferring the ownership to VHS. The effigy is still the property of VHS, and is on display at the Alliance Center in downtown Abbeville.

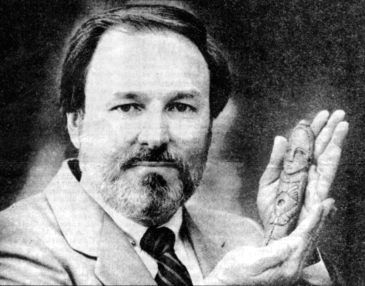

Gary Theall displays the Morgan Effigy in 1986

(Photo from the Times-Picayune)

Arrangements were made with the Lower Mississippi Survey, through Harvard University's Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, with the aid of a grant from the National Science Foundation, to conduct an archaeological excavation of Mound 1. Dr. Stephen Williams, Peabody Professor of American Archaeology, Dr. Ian W. Brown, Associate Curator of North American Collections, Dr. Jeffrey P. Brain, of Harvard University, Richard S. Fuller, Jr., of the University of Alabama, and Diane E. Silvia-Fuller of the University of South Alabama, were the persons primarily in charge of the planning, supervision, excavation, and chronicling of the work. All took an active part in the project in their various capacities.

The excavations began on August 12, 1986. After two and a half months of digging, filtering, washing, photographing, charting, and recording, the archaeologists reported their findings. The summit of Mound 1 once supported a large, circular house about nine meters in diameter. There was evidence of abundant post holes, perhaps indicating successive rebuilding. A fire hearth complex occupied the center of the summit, with some evidence that it was used for fired clay pottery manufacture. Numerous decorated and varied pottery shards were recovered, indicating extensive trade between Native American cultures over a large area of the Gulf Coast. Some human bones were found, but the mound was not used primarily for burial purposes. Most of the other artifacts recovered were worked bone points and tools, and worked shells; only a few stone arrowheads and tools were found.

While everyone connected with the excavation was grateful that whatever information the mound held was recovered and recorded, a slight sense of disappointment prevailed due to the failure to find a work of art comparable to the Morgan Effigy. On the other hand, any expectation of finding something as magnificent as the Morgan Effigy would have been unrealistic.

In their final report, archaeologists Fuller and Silvia-Fuller included an appendix on the Morgan Effigy, and described the effigy as follows:

The most fabulous artifact discovered so far at Morgan did not come from any of our excavations. It is an exquisite human effigy carved from a piece of deer antler. The artifact was found by a local resident of Pecan Island in a load of fill obtained from the leveled Mound 2. Although this rather exotic piece was discovered after removal from its primary context, it is believed to be authentic and to have indeed originated in Mound 2. The effigy has come to symbolize the significance of Morgan. It is stylistically unique for the region and, to our knowledge, is the only piece of non-ceramic Coles Creek art of its kind ever found.

The effigy was expertly crafted following the natural contours of the antler. It depicts an adult male with an egg-shaped-head and a high forehead. The hair is shown as being rolled along the sides with a top bun and a back bun. The eyes are carved shallow ovals with incised brow arches. The eye sockets exhibit a faint green stain, perhaps indicating the former presence of copper inlays. The proportionally large naval may have once been inlaid as well, perhaps with shell. The ear lobes are slightly extended and are pierced. The high-bridged nose and squared mouth with individually carved teeth are realistically shown. The arms are long and bent at the elbows, the forearms coming forward. The hands have folded thumbs and are holding a tabular-shaped object over the groin. The clavicles, scapulae, and sternum are clearly shown. The rib cage is represented by four pairs of ribs in front and three pairs in back. The pronounced spinal column consists of eight vertebrae. The lower portion of the effigy is more stylized. A small horizontal incision at the base of the spine depicts the buttocks, while vertical lines in the front and back form the legs. Incised lines encircling the base delineate the feet, and a series of short lines represent the toes.

The base of the effigy is socketed and is believed to have been mounted on a staff or baton. It is significant that human bone was also reported from the same load of fill that produced the effigy. This is slim evidence that it may have accompanied the burial of a ranking individual. The shape of the mouth and the protruding bones suggest a desiccating corpse. The carving, therefore, may be a representation of the deceased or of death in general.

The description was accompanied by the enchanting sketches of the Morgan Effigy drawn by Diane Silvia-Fuller, shown below. The frontal view sketch has become the logo of the Vermilion Historical Society.

|

|

|

| Front | Back | Left |

The Morgan Effigy is on display at the Alliance Center, 200 N. Magdalen Square, Abbeville, Louisiana.