Christian

George Honold:

Christian

George Honold:by Kenneth A. Dupuy

When the Angel of Death caught him by surprise, Christian George Honold was in his 55th year. From my vantage point, he was relatively young. Although he had lived in Abbeville for only 25 years, Christian George Honold designed many of Abbeville's most distinctive landmark buildings. They have helped to define and to distinguish our city. I don't know much about Honold as an individual, so we must take measure of him mostly from the buildings he gave us. Once you hear mention of them, many of you will recognize them immediately. Although constructed between 77 to 102 years ago, most his buildings still grace Abbeville with their unique architectural details, and they are still in use.

George Honold, as he was generally referred to, was born in New Orleans. How did he end up in the much smaller, less culturally and historically significant town of Abbeville? Did relatives lure him here, or were his services requested? I don't know.

When Honold died, his life and his influence on Abbeville received barely any attention by our local newspapers: the Abbeville Progress and the Meridional. In fact, their two obituaries included a total of only 24 lines and 144 words. From these obituaries, we learn that he died on February 14, 1925, at his Abbeville residence, and that his remains were brought to New Orleans for interment, "in the family tomb." According to the Abbeville Progress, "Mr. Honold was an architect of much experience..." That was all that either newspaper had to say about his chosen profession and his mark on Abbeville. There was no mention of the architectural legacy that he left behind in Abbeville, and elsewhere. This journey into the past is an effort to correct that slight.

Elsewhere, I have characterized architects as having the minds of mathematicians and the souls of artists. Like many of you, I'm particularly appreciative of their contributions to the quality of our communities. Their artistic works are to be seen, to be lived in, and in them, we practice our occupations. Architects' works are functional art. Unfortunately, these works of art are seldom signed. Too few cornerstones have the names of those who designed the buildings. So, it is easy to forget, and to be unappreciative of the fact that buildings don't just sprout up like plants; they must be carefully planned for the purposes for which they are intended.

George Honold designed, as we've noted above, many of Abbeville's landmarks that still survive and that call attention to themselves, and to Abbeville. We will visit only those buildings that we know with certainty Honold designed. Until recently, I was uncertain as to whether Honold had designed any homes in Abbeville. However, I recently found that on January 30, 1915, the Abbeville Progress reported on his recovering from a bout with pneumonia. It also reported, "Mr. Honold is an architect, and made the plans for many of the homes and buildings in this city." If only we knew which residences he designed, and which of them are still in existence.

For years, unfortunately, I've credited George Honold as the architect of Abbeville's 1891 courthouse. Only recently, when I noted he died at the age of 54, did I realize that Honold could not have drawn up its plans. He would have been only 20 years old in 1891. Further research shows that Douglas Southwell, from New Iberia, was the project architect for that courthouse. The architectural plans seem to have been drawn by John Hannan & a Mr. Pulford, in 1888. In 1893, Southwell was also the architect for the building that now houses Black's restaurant. Solomon Wise had hired Southwell to construct this building. Southwell was also credited as being the architect for the first structure built for the Bank of Abbeville, in 1896. This building—located just north of the present Frank's Theatre—was destroyed in the monstrous fire of 1903 that destroyed numerous buildings, businesses and offices on the south side of Concord Street, as well as several buildings on State and Jefferson streets. It was because of that fire that a new building for this bank had to be constructed. George Honold was the man for this job. Coincidentally, his office had been in the bank's building destroyed by this fire. However, we should first visit the buildings in Abbeville that he is known to have designed prior to the second Bank of Abbeville building.

Honold had spent the early part of the year 1900 in Crowley. While there, he was drawing up plans for the mill of the newly-founded Abbeville Rice Mill Co. Land had been purchased from Gus Godchaux in the latter part of 1899. Most of the stock—$30,000 of $40,000—had been purchased by a couple of businessmen from New Orleans and by A. Kaplan of Crowley. Perhaps Honold had been drawing the plans for Abbeville's rice mill under the watchful eye of Mr. Kaplan, a heavy investor in that enterprise. The Meridional noted that George Honold had been in Crowley engaged in "architectural work" for the Independent Rice Mill. Had this job given Honold his first experience with the large buildings required for rice mills? I don't know, but many of his structures seem to have been of enormous proportions, as we shall see.

In late March 1900, ground had been broken for the erection of the rice mill in Abbeville. It was to have cost $70,000 and was to have taken 1½ million bricks to complete. It was certainly time for Abbeville to have its own rice mill. Crowley had long had mills, and even Gueydan had one. With the construction of irrigation canals like the Hunter Canal, rice could and would be grown in our vicinity. A. Kaplan, as well as some of our local businessmen, realized that a rice mill would stimulate the growth of our local economy.

H. K. Robinson, a local contractor, and his crew completed the construction of the mill in three months, and by September 1900 the Abbeville Rice Mill was in operation. Where once only wagons transporting cotton, sugar cane, and corn were seen trudging down Abbeville's dusty/muddy streets, now convoys of wagons, filled with rice, would be seen plodding along the streets of town. A new, golden crop would take its place at the table, alongside these other crops. Rice would soon vie for its share of attention and consideration.

Abbeville Rice Milling Company

A century later, the first building in Abbeville known to have been designed by Honold—Abbeville's first rice mill—still stands, just south of the old railroad freight depot, on the edge of the picturesque Vermilion River. The mill continues to be used by the rice industry, but in a modified use. Today, it serves as the Riviana Company's packaging plant. In addition to packing the Mahatma and Water Maid brands of rice in packages of various weights, this plant also packages rice for several private brands.

Obviously, Honold's architectural plans had impressed some of Abbeville's influential and prominent citizens. In 1902, he was given the contracts to design a three-story jail, and Abbeville's first high school building, which was also to be three-stories high. It is possible that taller buildings in Abbeville weren't feasible at that time, because of the limitations of local construction methods and building supplies.

Let's visit the previous jail which was built in 1882, on the northeast corner of the courthouse square. In 1900, the Grand Jury characterized this aging, decaying structure as "a disgrace to civilization." I'll quote just one sentence from this jury's report. Of the two prisoners lodged there at the time, the report stated that "these two humans, one black and one once-white, hang on to life, eating, drinking and sleeping with the vermin they breed, with the offal they excrete, and the stench they create." It was definitely time for a new jail. However, it would not be until 1902 that Honold received the contract from the police jury to draw up plans for a new jail.

Construction of the jail was begun on the southeast corner of the courthouse square in October 1902. Youngblood Bros. were the builders; Vernon L. Caldwell did the brickwork. The jail was turned over to parish officials near the middle of February 1903. This building was described as being “almost as solid and strong as the rocks [sic] of Gibraltar." During the construction of the jail, the prisoners were housed in Lafayette and New Iberia’s jails.

To my knowledge, this jail was used until 1951, when it and the courthouse were razed to make room for our current courthouse, which housed prisoners on the third floor for many years. For nearly a half century, another of Honold's buildings helped to define Abbeville.

George Honold, the "artistic and skillful architect," was hired to design and supervise the construction of Abbeville's first high school building, according to a May 1902 issue of the Meridional. However, the Abbeville High School Building Committee had previously accepted Honold's plans in December 1901.

For decades, concerned citizens had sought such a structure for Abbeville. Numerous public meetings had been held at the courthouse for this purpose. Finally, in September 1901, 103 of the eligible 171 property owners approved unanimously its construction.

Initially, the building was to have cost $10,000. However, when the bids were opened, the lowest bid was for $16,000. The town and the police jury had previously agreed to split the $10,000 cost. The town then agreed to pay its half of the additional $6,000, but the police jury refused to contribute additional funds. I don't know where the additional capital came from, but by the time of the building's completion, construction costs had risen to $18,000. Honold, according to the Meridional, had not been blamed for the increase in the costs of construction.

As designed, the high school was to have housed 10 grades and was to have had a capacity of 400 students. It also had separate playgrounds for the boys and for the girls. In keeping with the times, only white children, between the ages of 6 and 18, were eligible to attend.

Like the new jail, the high school was completed about the time of Abbeville's largest fire—February 19, 1903. The students crossed the school's threshold for the first time on February 23, 1903. The first school session closed on June 18, 1903. That was a rather abbreviated session, to be sure. However, Abbeville could finally point with pride to its own high school building.

Initially, there had been some opposition to the school’s location. Some citizens complained that the location would be too near the busy, noisy railroad tracks. Others probably felt that it would be too close to the silent and somber Masonic Cemetery. However, these objections were overcome by those in the majority.

The student enrollment grew much faster than was anticipated. By September 1906, the first grade class had to be moved to the Masonic Hall on State Street, because of limited space at the high school. At this time, the cost per student in the high school was $1.25 per month. In 1999, this cost had risen to about $450 per student, per month. Is this what is meant by "higher education"? Kidding aside, there is little comparable to the schools of today and those back then. The structures are more numerous and more substantial than in those days. Today, there are many more teachers, who are paid considerably more than $40 per month. Supporting employees are enormous in number. From just these few comparisons, it is understandable why the cost of education is much greater today than it was in 1906.

In 1908, the schools at Abbeville and Gueydan were approved as high schools by the State Department of Education. The Meridional noted that Vermilion parish "now has two of the fifty high schools in the state." As early as 1898, there had been a high school in Henry. I don’t know what became of it.

By 1912, Honold had been contracted once more by the parish school board to draw up plans for another structure to be built on the high school grounds. It was to be a five-room structure for 300 students. Imagine! That means that there were to be 60 pupils per classroom. This "school house for the primary grades of the 3rd ward" was described as being one of "no show but lots of solid comfort and convenience." Honold had to design the structure within the constraints of the funds available for its construction.

Also in 1912, Miss Eugenie Honold, George's sister, and Mrs. J. R. Kitchell, wife of the former Superintendent of Education, solicited funds for the erection of fire escapes at the high school building. It appears that such had not been installed previously, as a comment was made about the parents being able, finally, to be relieved about their children's safety, once these "escapements" were installed in May 1913.

Abbeville High School with fire escapes and annex

Sometime in 1926 or 1927, Abbeville finally built another high school, and at that time, the high school curriculum consisted of 11 grades. It was certainly time for a new school building. In 1921, at the high school building that Honold had designed, there were three fourth-grade classes. Two of them had to be taught outdoors on the school grounds. Hopefully better arrangements were made eventually.

Once the new high school opened, the first high school structure—the one designed by Honold—and its annex continued to house the lower grades.

I don't know when the first high school building stopped functioning as a school. The Vermilion Parish School Board moved into this building in the 1940s or 1950s and converted it into an office complex. Its administrative offices, in 2003, still occupy this structure.

As we saw earlier, the fire on February 19, 1903, destroyed numerous buildings including the Bank of Abbeville's building. This two-story structure had been constructed in 1896, just north of the present site of the Frank's Theatre. Despite its having been constructed of brick, the bank building could not withstand the voracious hunger of that fire.

George Honold had his office in that doomed building. Did that fact cause him to receive the contract to design the bank's new building? Most probably not. It was more likely that his previously designed buildings had caught the attention of the officers of the Abbeville Investment Company. On April 8, 1903, only three weeks after the fire, this company was organized with a capital of $30,000. Gus Godchaux was its President, while Frank Godchaux, Sr., was the Vice President. L. O. Broussard, cashier of the Bank of Abbeville, became secretary of the Abbeville Investment Company. Broussard invested $15,000 of the $30,000 capital stock. The Godchauxs each invested $5,000. Also on the board of this new company were Eli Wise, President of the Bank of Abbeville, and Emmet Putnam, Sr. These two men each invested $2,500. The company bought the land for the bank from Gus Godchaux, Frank Godchaux, Sr., and from the Bank of Abbeville for a total of $9,000.

The Abbeville Investment Company selected George Honold to design the plans for its two-story brick structure, which was to have offices on the second floor. The first floor was to house the Bank of Abbeville, and "front stores" were to cover the "balance of the space." James A. Petty was given the contract to build this structure for $26,000. Petty had constructed the first mill for the Planters' Rice Mill, in 1902.

Early in June 1903, ground was broken for the construction of the Abbeville Investment Company's building. Later that month, twenty carloads of sand, which was to be used in the construction of the building, were transported from the sand bank on the Trinity River, near Liberty, Texas. Surely such soil from my home state lends something to this building's uniqueness. I was unable to determine exactly when the building was completed or when it was moved into, but the cornerstone reads "MCMIII," or 1903 for those of us who aren't Romans.

The history of the Bank of Abbeville and Trust Company's building is too long and varied to cover here. Suffice it to say that besides housing the bank, several mercantile businesses have been housed here. Stauffer Brothers and the Stauffer-Godchaux Co. were two of the first to occupy the space of the "front stores" of the building. One other business of note to have occupied that space was West Brothers. This store opened its doors to Abbeville in 1937.

Stauffer's display at Concord Street entrance

Also occupying rooms in this building was the Weekly Herald. On January 7, 1905, it was housed in rooms 17 and 18. The following year, the Herald was purchased by Dr. C. J. Edwards, owner of the Meridional, at a sheriff’s sale and it was moved to another location. In April 1904, The Cumberland Telephone Company moved its operations “into the new quarters over the Bank of Abbeville where they are handsomely fitted up with a new switchboard and new furniture.” I don’t know how long this phone company remained in this building.

In 1909, the Abbeville Investment Co. sold the building, in what the Meridional characterized as "one of the largest deals in real estate." The Stauffer Brothers bought the "stores now occupied by them on Jefferson and Concord streets for $22,000." The Bank of Abbeville "paid $13,000 for the portion of the building at the corner occupied by it," according to the January 16, 1909 issue of the Meridional.

Few people may recall, or may be aware that the 1890-built courthouse in Abbeville had a lion's head glowering from its west wall, above the second story level, over the main entrance. From photos, and from May Mayeux's recent painting of this courthouse, the head reminds me of the lion-head knocker that is seen on Scrooge's front door in some of the film versions of "A Christmas Carol." This high relief sculpture looks as though the lion had been in the process of sticking its head outward through the wall of the courthouse, when suddenly the wall solidified and trapped the lion's head, emerged only partially.

Lion's head on old courthouse in Abbeville

In any case, the Bank of Abbeville was not to be outdone. At one time, it could boast of its own creature: a large metal eagle—with wings extended—perched upon a tall flagpole, high above the bank building . In 1917, this eagle was gilded and the flagpole was painted. How impressive it must have been to see our national bird silently, but vigilantly guarding one of Abbeville's most distinctive buildings, as though the structure were its own aerie. While that eagle has long since disappeared—as have numerous other local landmarks—the twin towers of George Honold's bank building still garner—nearly a century later—the well-deserved admiration of Abbevillians and tourists alike.

In 1912, the wood floors, and the bottom of the counters of the bank had to be replaced. Damage to them from "Argentine ants and dampness arising from the soil" necessitated this replacement. New wood floors were placed on top of "solid concrete." Near the end of 1917, a new roof was put on the bank.

On December 12, 1936, the Meridional reported a major face-lift for the bank building. The refurbishment included "refinishing of the cement furnishings, the painting of the bricks, and the trimming of the windows." I wonder if complete brick walls, or only portions of them were painted, and what color was used. The building was also being renovated for the West Bros. store that would move in, in early 1937. Additionally, nine offices were added on the second floor. Before these rooms were added, the upstairs of the Bank of Abbeville building was partly occupied by the Southern Bell Telephone Company, and by Felix J. Samson, an attorney.

Let's go now to another of Honold's buildings. On April 8, 1902, ground was broken for the Planters' Rice Mill Company's mill. When I first read about it, I wondered why Abbeville needed two rice mills. However, I learned that by that time, Crowley had nine rice mills. Local investors in this company were mostly Abbevillians, but also individuals from numerous other communities bought shares in it. W. H. Hunter, Jr., of Milton, La., purchased 50 shares, while Frank Godchaux, Sr., bought 40 shares of stock; each share's value was $100. W. H. Hunter, Jr., became the company's first president, P. B. Roy the first vice president, and D. L. McPherson its secretary and treasurer. By 1905, the capital was increased from $50,000 to $75,000. In June 1905, Gus Godchaux was president, J. N. Greene was vice president, and Frank Godchaux, Sr., was the company's treasurer and general manager.

By September 1902, the mill was operating. I could not find who the architect for this structure was. However, I learned by accident that Honold and G. Gauthier had drawn the architectural plans for the Planters' Rice Mill Company's second mill. And why did it need another mill? As some of you might have guessed, Abbeville's nemesis, fire, destroyed the first mill. At 7:30 p.m., on April 26, 1904, less than two years after it began operating, the mill was destroyed by fire. It began insidiously in the engine room. In less than an hour, the building was but heaps of smoldering ashes, wisps of smoke, and crumbling brick walls. This fire almost had an added trophy: a human sacrifice. Frank Godchaux, Sr., who was probably the manager of the mill, had gone into the burning building to retrieve some papers. Smoke inhalation caused him to fall unconscious. Fortunately, an African-American man, who was unnamed by the Meridional, pulled Godchaux from what could have been Godchaux's pyre.

Within a month, Honold and Gauthier had drawn up plans for a new mill. Today some of those original construction documents can be seen hanging in Riviana's headquarters. Several months ago, I'd seen these plans, but they had no special significance for me. Then, sometime later, I noticed that Honold and Gauthier had drawn them; here was yet another of Honold's buildings gracing Abbeville's small, but distinctive cityscape. By September 24, 1904, the construction of the second Planters' rice mill was nearly complete.

Planter's Rice Mill, Abbeville, Louisiana

The mill has undergone some obvious modifications. For example, many of its previous doors and windows have been bricked in. However, this structure is still being used to mill rice: one of this area's leading crops.

In 1905, Honold and G. Gauthier advertised as architects in Abbeville's short-lived Weekly Herald. By May 1905, Honold and Gauthier, "the well known Abbeville architects" had received contracts for high school buildings in Arcadia and Cheneyville, buildings for the Bank of Bunkie and the Bank of Lafayette, as well as "business buildings at Jeanerette and Lafayette." Sounds as though 1905 was a banner year for these men. Surely it was Honold's and Gauthier's previous architectural works, rather than their advertisements, that caught the attention of those requesting their expertise in 1905.

Let's leave Abbeville briefly and visit Lafayette where another of Honold's buildings is still being used some 90-plus years later. I'm talking about the building that is commonly referred to as the "old Guaranty Bank." While it is true that Guaranty Bank was probably the last banking institution to be housed in this building, the original tenant was the Bank of Lafayette.

The Bank of Lafayette's second building sits on the corner of Congress and Jefferson streets. However, when this structure was completed and moved into, on May 31, 1906, Jefferson Street had another name: Pierce Street.

Construction of the building was delayed considerably due to a Yellow Fever epidemic in other sections of the state. In 1905, Lafayette's quarantine against towns where this marauding killer was taking lives—over 400 victims were claimed in New Orleans alone—was stringent. Even though it was known by then that certain mosquitoes carried the disease, many items, including construction materials, were not allowed to enter Lafayette. Ground was finally broken for the construction of this bank building at the beginning of December 1905.

Other than the notice in May 1905 that Honold and Gauthier had received the contract to draw up the plans for this building, I was unable to find any other verification that these individuals had done so. However, I made comparisons of the photograph of the Bank of Lafayette's second building with the photos of the Bank of Abbeville, the Peoples Bank and Trust Company, the Fenwick Sanitarium, and the Masonic Hall, all buildings that we know were designed by Honold. To me, these latter buildings and the Bank of Lafayette's second building show strong architectural similarities that cannot be written off solely as the architecture of the period. Columns grace the entrances of the Bank of Lafayette, and of the Peoples Bank and Trust Company. Columns enhance the entire front of the Fenwick Sanitarium, and there are huge columns in front of the building of the Abbeville Lodge No. 192, F. & A.M. Ornamental cupolas are to be seen on the Fenwick Sanitarium, the Bank of Lafayette, and in an illustration of the Peoples Bank and Trust Co.

If only I were more versed in the language of architecture, I might be able to compare the various architectural elements and make a more accurate judgment about the authorship of the Bank of Lafayette's second building. I believe, however, that Honold & Gauthier—as suggested by the report in the May 1905 issue of the Meridional—drew up its plans. I still lament the fact that too often buildings do not have the names of the architects, the contractors, etc. listed somewhere on buildings. Other works of art have the names of the artists listed.

Let's return to Abbeville to visit another of Honold’s buildings. Dr. F. F. Young had been treating individuals who had drug and liquor "habits" as well as those suffering from "nervous diseases” at his Fenwick Sanitarium for years. In 1902, he had a building constructed specifically to house his sanitarium. Prior to this time, his facility had been housed in various homes in Abbeville.

As so often happened to other buildings in Abbeville, fire destroyed Dr. Young's sanitarium. This three-story building burned down on the night of February 6, 1906, during a blizzard. Dr. Young selected George Honold to design another sanitarium. Like the legendary phoenix, it would rise from the ashes of the previous sanitarium. It, too, would be located at the corner of East and St. Victor streets. This Fenwick Sanitarium was probably the only wooden structure of such major proportions that Honold designed. The Meridional reported that its dimensions were 286 feet by 100 feet. These measurements probably did not include the gym, which was set off from the main building.

Fenwick Sanitarium and gymnasium

By the end of July 1906, Mike B. Gordy, contractor, and his workers had nearly completed the building. A formal dedication was held for the new Fenwick Sanitarium on January 28, 1907. It was one of the grandest of celebrations ever to have occurred in Abbeville, up to that time. The Meridional described the event as "the most memorable occasion the town of Abbeville has ever known. Never...have so many distinguished citizens, the highest in religious and official station, been gathered within her gates at one time and for one and the same purpose.” Archbishop J. H. Blenk, Governor Newton Blanchard, and the mayor of New Orleans gave speeches. Abbeville's mayor, J. R. Leguenec, and District Judge M. T. Gordy also addressed the crowd.

Despite the grandness of the occasion, there doesn't seem to have been any mention made of the architect of this magnificent structure: George Honold. Not much has changed since that time. Architects still don't receive the credit they deserve. In fact, in the December 1999 issue of the magazine "Architecture," the editorial made a similar observation. It noted that in a three-hour program celebrating the $70 million renovation of Radio City Music Hall, not one mention was made of the architects.

These "opening ceremonies" for the sanitarium took place at the courthouse, while "over five hundred persons" were entertained that night at a banquet at the sanitarium .

Fenwick Sanitarium 1907 postcard

In later years, this building was divided into a sanitarium and a hotel. Eventually it was transformed into the Palms Hospital. This "proud old building in its declining years" met an ignoble ending, in 1965, according to an unpublished paper by Mrs. B. B. McClellan. She stated that the Palms was sold for $10,000 and was razed. Mrs. McClellan added that parts of the building, like bricks and stained-glass windows, were recycled and can be found in different sections of Abbeville. She concluded, "So much of the old Palms seems scattered with the wind." Today the block upon which the Fenwick Sanitarium stood for nearly sixty years is unused except by Mother Nature. However, this site has been selected to become the location of a new public library. Hopefully, the architect of the proposed library will receive deserved recognition.

And now we come to what I consider to be C. George Honold's greatest architectural work: the current church of St. Mary Magdalen. It sits on the site of five previous Catholic churches, including the LeBlanc home that Father Megret had converted into a chapel, and a church that he had constructed on this site, in 1848. The last church to stand on this site, prior to Honold's church, was built in 1884 by Father Mehault and his parishioners. Like so many other buildings in Abbeville, it was destroyed by fire. The rectory—adjacent to the church—was also reduced to smoldering ashes on the fateful night of March 22, 1907.

Initially, Father Laforest and his congregation were financially unable to construct the $50,000 church that they envisioned. Instead, a 50 by 100 foot, temporary wooden church was built on the east side of Main Street, just north of where Waterloo Street intersects with Main Street. Father Laforest named this church St. Anne's—or St. Ann's [I've seen both spellings]—in honor of the patron saint of Canada: St. Anne de Beaupre. It would serve the Catholics as their place of worship for nearly four years, until the construction of the current church was completed, and was first used.

George Honold was named as the architect for the new church in the January 30, 1909 issue of the Meridional. Shortly thereafter, the foundation of the structure was laid. However, it would be another year—in March 1910—before work was begun on the construction of the church. The Meridional reported that Honold, Father Laforest, and the church wardens supervised the work. I presume that Honold was the day-to-day supervisor and that he reported to the others.

St. Mary Magdalen Catholic Church, Abbeville, Louisiana

Finally, in February 1911, nearly a year later, the church saw its first High Mass, wedding, and funeral. The church, as indicated by the cornerstone, continued to be called St. Anne's. This fact was reported by the Meridional. For several years afterward, whenever this church was mentioned in the newspapers—the Meridional and the Abbeville Progress—including Mass schedules, it was referred to as St. Anne's, or St. Ann's. In 1918, following the end of World War I, the end of the world-wide influenza epidemic, and the completion of the interior of the church, the name was changed back to St. Mary Magdalen’s church.

Despite the fact that the church was being used for religious services beginning in February 1911, it would not be until 1918 that the interior of the church received extensive, finishing touches. Until that year, piecemeal work was done on the interior. It is possible that the work on the interior was done as additional funds were raised. Today, visitors to the church will note that some of the stained-glass windows are dated. Some of them, apparently, weren't installed until 1917. Father Laforest, under whose pastorate this church was conceived and constructed, did not see the completion of this magnificent structure. He died in 1915, three years before the completion of the interior. I wonder if Honold continued to supervise the interior design and work through 1918. Whatever the case may be, this magnificent edifice will surely be held as George Honold's greatest architectural design.

|

|

|

|

St. Mary Magdalen |

St. Mary Magdalen |

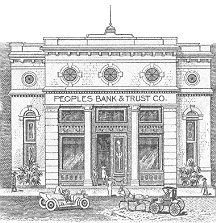

Since Abbeville had supported two banks for more than a decade, it was felt that it could support yet another banking institution. In July 1911, the Peoples Bank and Trust Company was organized. It purchased a lot 27 feet, 4 inches—north and south—by 120 feet—east and west—on the west side of State Street, just a few doors south of the intersection of State and Lafayette streets.

A week after the Meridional reported this transaction, it disclosed that the new bank's directors had accepted George Honold's plans for their new bank building. By this time, Honold had designed several prominent buildings, so these men knew that they weren't buying the proverbial pig in a poke.

This lot had been purchased from E. M. Stebbins, who, by the way, became the bank's president. O. J. Chauvin became first vice president, while P. U. Broussard was elected second vice president of the board. J. Camille Broussard was the cashier.

On August 14, 1911, R. J. Montagne, a local contractor, broke ground for the new bank building designed by Honold. By December 9th, it was nearly completed. Plans were for it to open for business on January 2, 1912, with $50,000 capital.

If only I had better knowledge of architecture, then I could describe better the front of this bank as it looked originally. I'll do the best I can. Over the entrance, there was a small portico. The beam across the front was supported by four columns. The two center ones appear to have been marble columns, while the outer ones were constructed with bricks. These bricks seem to have been the same type as those forming the front wall of the building. I recall reading that the bricks were white, "pressed" bricks. Above the beam of the portico were three small circular indentations. In a 1916 illustration of the bank, these elements appear to have been stained-glass windows, looking much like the round windows on the front of the St. Ann's-St. Mary Magdalen church that Honold designed only a year or two prior to this bank building. There were also two similar "windows" at the top of each end of the bank building's front wall. However, in the photos that I've seen, these round indentations have no window panes. Two narrow, but tall cathedral windows provided light on the north and south sides of the entrance. In the illustration, they also appear to have been stained-glass windows.

The entrance was a set of double doors over which a large window spanned the width of the double doors. On either side of the doors were large show windows, in the illustration. To me, another outstanding architectural feature in the 1916 illustration of this building was a cupola. This feature is not seen in the photos. These photos were taken too close to the front of the building to show any features on the roof.

The design of the windows on both sides of the door changed over the years. In 1939, for example, they had become two large panes in each of the windows. A later photo shows that these panes were replaced by four panes in each window's opening.

Above the columns of the portico, the names changed. Originally, this beam, or architrave, bore "Peoples Bank & Trust Co." From 1930 to 1933, "Kibbe & LeBlanc" replaced the previous name. Sometime in 1933 or in early 1934, "City Hall" began to grace this architectural element, which could be compared—crudely—to a theater's marquee. However, in this case, it was announcing the current business or organization that was housed in the building.

The Peoples [I've seen it spelled as "Peoples'" also] Bank and Trust Co. provided financial support to the community from 1912 to 1926, although the composition of the board and the officers changed over the years. In October 1913, the Abbeville Progress listed the directors as O. J Chauvin, E. M. Stebbins, P. U. Broussard, F. Joubert, Henri Sere, H. Hotot, D. Silverman, J. E. Nettles, Joe Immergluck, Jake Immergluck, and Tom Fleming. The officers remained the same as in 1912.

In 1919, E. M. Stebbins resigned as president, although he remained on the board of directors. J. Camille Broussard resigned as cashier to run for clerk of court. John Nugier became president, O. J. Chauvin, first vice president. R. J. Montagne, the contractor and builder of the bank building, became second vice president.

Over the years, these directors and officers guided the bank through good times and tough ones, too. For example, in 1918, Abbeville had just experienced the loss of human life caused by World War I and the pandemic Spanish Influenza. On a more upbeat note, 1918 saw the completion of the interior of George Honold's magnificent structure: the St. Mary Magdalen church. The bank would also witness the construction of the Catholic presbytery in 1921. However, I don't know if that structure was designed by Honold. In 1923, the bank would witness the completion of yet another of Honold's landmarks: the Masonic Hall.

In June 1923—around the time of the dedication of the new Masonic Hall—the Peoples Bank ran an ad in the Abbeville Progress. The ad promoted the advantages of a checking account: "1. It safeguards your money; 2. It makes possible payments by mail; 3. It provides a record of expenditures; 4. It costs nothing." My, how times have changed! Anyway, the ad encouraged "opening an account here."

In 1925, the Peoples Bank was assuring the public that its money was safe from burglars. The bank's officers and directors had had "burglary protection" installed." The system consists of a mechanical and chemical resistance, which will combat the burglars with their acetylene torch or any other burglarious [sic] attack."

Despite the efforts of the directors and officers at the helm, this financial ship struck an iceberg in the sea of economic perils and sank. On December 18, 1926, the Meridional ran a story under the heading: "Peoples Bank Closed Wednesday." This was Abbeville's first bank failure. The "State Bank Examiner" ordered it closed. An unnamed bank officer was quoted as saying that he didn't believe that the depositors would lose anything. It was also "believed that when the tangle is straightened out it will be an easy matter to effect a reorganization." However, such was not to be. By May 1927, another story in the newspaper was titled "Peoples Bank & Trust Co. in Liquidation." The bank had had offices at Abbeville, Kaplan, and Gueydan. I don't know how the depositors fared. I do recall having been told by one individual that he had lost money when the Peoples Bank and Trust Co. closed forever.

Like the two other banks in town—the First National Bank, and the Bank of Abbeville—the Peoples Bank had stoked the financial fires of the community, keeping the town and its citizens moving forward. Now, in 1926, it had run out of fuel and was no more.

I don't know how the building fared for the next few years. It may have simply lain fallow awaiting cultivation by another firm. On January 11, 1930, the Meridional reported that the firm of Kibbe & LeBlanc had purchased this building, the lot, and the fixtures for $4,300. On March 8, 1930, one of our local papers—I forgot to note which one—reported that the Kibbe and LeBlanc firm had new offices in the former bank building. This firm had been in existence a "trifle over a year," and it dealt "strictly in insurance and fidelity bonds." This firm had had its offices in the relatively new Audrey Hotel building, facing Concord Street, beginning in January 1929. This business was composed of J. E. Kibbe, N. J. LeBlanc, and Frank Godchaux, Jr. While LeBlanc was to operate as the "inside and outside man," Kibbe was the "executive." Godchaux was to act as "associate." A new "banner," would now "fly" over Honold's building: "Kibbe & LeBlanc." It would remain there for the next three years.

On June 10, 1933, the Meridional reported that on June 5, the town council had authorized Mayor P. U. Broussard to purchase this building for the city for $3,000, from Kibbe, LeBlanc, and Godchaux. You will recall that Broussard had been on the original board of the Peoples Bank. With a new and different authority, Mayor P. U. Broussard would now play yet another major role related to this building.

The Kibbe & LeBlanc firm had not gone out of business. In April 1933, Kibbe bought LeBlanc's interest in the "well known Kibbe & LeBlanc Insurance Agency." Kibbe planned to move the business to his law office on St. Charles Street, according to the newspaper.

Before the municipal offices could be moved into its new building, renovations were made, mainly to the interior. On June 19, 1933, the "City Council moved into and took permanent charge of its new quarters" in the old Peoples Bank building. "Those of the city employees who are located at the new quarters are well pleased with the change," according to an article in the Meridional, on June 24, 1933.

The previous city hall—located on the north side of Magdalen Square, on the corner of Jefferson and North streets was razed. It had been used originally by the Abbeville Hook and Ladder Co.—Abbeville's first firefighting unit—and had been built in the early 1880s. The lumber from this decades-old structure was put to good use. Much of it was used to build "bath houses" at the public swimming pool at Godchaux Park. The pool would be officially dedicated and opened in July, 1933. According to a resolution passed by the city council earlier in June, any remaining lumber was to be "donated towards the erection of a stadium at the New High School."

On September 2, 1939, the Abbeville Progress published a photo of City Hall. The facade of the former bank building was virtually unchanged except that "City Hall," in bold lettering above the marble pillars, proclaimed new ownership of the building. Beneath this photo, it was stated that there had been a complete remodeling, "including repairs to the walls, complete repainting, fitted up with venetian blinds and the addition of new furniture." None of this remodeling was apparent in the photo of the front of the structure. It was also reported that, "Meetings of the Mayor and members of the Town Council are held here on the first Monday of each month with special meetings at the call of the Mayor when necessary. The Mayor's court is also held here."

Peoples Bank building as City Hall

As we learned earlier in this journey, City Court occupies this building at the present time. A plaque on the front of the building states that the "construction" of the City Court was done in 1964, when Young A. Broussard was Mayor, and Marcus Broussard, Jr., was City Judge. At that time, the building's identity was as completely altered as that of an individual in a witness-protection program. Although Honold would surely be delighted to see that his bank building continues to play an important roll in the community, I'll bet that he would be upset over its full-scale architectural makeover. Young A. Broussard told me that he believes that the municipal government moved from the bank building to its Charity Street site in 1961. Despite that move, the city council continued to meet in Honold's bank building until City Hall relocated in the old Audrey Hotel building, in 1990.

While we're on the subject of City Hall, let me remind everyone that a city hall was almost built on Magdalen Square. In fact, the foundations had been laid before construction was halted by a court battle between the Abbeville municipal government and the Vermilion Parish Police Jury. This incident, if it can be called so, occurred in 1957. Imagine how different Magdalen Square would look today with such a building consuming so much space. There wouldn't have been much unused space for the public's recreation and enjoyment.

A market may have been built on the square, itself, in the 1850s. However, the description of it as being "on the square" may have meant simply near it, as we speak of buildings being built "on" a river or "on" Fifth Avenue.

One building was actually constructed on Magdalen Square, and as you might have guessed, George Honold designed it. It was built by R. J. Montagne, who had constructed the Peoples Bank building in 1911. The building on the square was built for the Vermilion Parish War Council, in 1918. It was paid for "by private subscription among members of the Council and merchants of town," according to the Meridional on June 29, 1918. That it was actually built on the square is proven by the following statement: "Magdalen Square holds an ornamental little building..." When it was completed in July, Samson Chauvin and his assistants in "WSS work" occupied it. Those initials stood for War Saving Stamps. Considerable amounts of such stamps, used to support the war effort in Europe, were sold in Abbeville, in the parish, and nationwide.

There was another reference to this building in October 1918, at a time when World War I was coming mercifully to an end, and when the Spanish Influenza Epidemic was claiming victims worldwide. At that time, Honold's building was called the "War Service Building." In late October 1918, a gust of wind slammed the glass door of the building against Zula Cluney's chin. The impact was great enough to smash the glass. Apparently Ms. Cluney suffered no major injuries. She was quoted as saying that "she is not unusually hard headed but that she has a strong chin which caught the blow." Ms. Cluney, by the way, had graduated from Abbeville High in May of that year. What an introduction into the “real world!”

I found one final reference to the building on the square, in the October 25, 1919, issue of the newspaper. The name of the building had been changed again, this time to the "Red Cross Office." Its mission was to house those who were "ready to investigate and relieve worthy cases," which, I assume, meant assessing the claims of destitute individuals.

How long did this building remain on the square? Was it moved elsewhere, and if it was, does it still exist? I wonder what Honold's structure on the square looked like.

And, now, we come to the last building that I know for certain Honold designed. It is Abbeville's Masonic Temple, which, like so many of his other structures, still serves proudly, in the year 2002.

As you will have noticed, Abbeville's enemy—fire—destroyed several buildings that Honold's structures replaced. This fact reminds me of the old saying, "It's an ill wind that blows nobody any good." However, the Masonic Temple that Honold's plans replaced was simply razed. It had been constructed in 1885, shortly after the courthouse was destroyed by fire. By an agreement between the Masonic Lodge and the Police Jury, it served as a temporary courthouse until January 1891 when a new courthouse was finally completed. As part of the agreement, the Masonic Lodge was allowed to use part of the second floor as a meeting room. Remember that the Abbeville Lodge had lost all of its possessions when the courthouse burned, because it was using the courthouse as a meeting site at that time.

Once the building on lot 46 (Megret Portion)—a lot purchased by the lodge in 1885—was returned to the lodge, this building saw a multitude of uses by other groups. For example, on December 15, 1892, a splendid banquet was held on the lower floor of the lodge. Following the ceremonies, at the railroad station, of the celebration of the coming of the railroad to Abbeville, the distinguished guests were transported to the Masonic Temple for a meal and for several toasts. In 1901, this building housed some practice sessions of the Abbeville Silver Cornet Band. In 1903, the local post office was housed in the temple for awhile, following the calamitous fire that destroyed the post office and dozens of other buildings.

In 1904, the lower floor of this hall held the presses and office of one of Abbeville's newspapers: The Herald. In 1914, when yet another fire claimed other structures, the Masonic Hall was used by a local pharmacist, P. H. Bailey, to hold a 3-day fire sale. The lodge hall served other purposes over several decades, but these examples illustrate the willingness of the local lodge to serve the public.

This Masonic Hall, built in 1885, came down thirty-seven years later. In July 1922, demolition began, virtually across the street from the much older Veranda Hotel. On September 4, 1922, the new building, though incomplete, was ready for the laying of the cornerstone. Following a meeting of the lodge, at a site unspecified by the newspaper, Abbeville’s lodge members and representatives from lodges at Crowley, St. Martinville, Lafayette, Lake Arthur, and New Iberia marched to the "New Temple." The cornerstone was laid then "according to custom of the ancient order of Free & Accepted Masons."

On June 23, 1923, the Abbeville Progress published a photo of the new Masonic Temple, and reported that its construction had cost $20,000. It was described as being "the finest Masonic Temple between the cities of Lake Charles and New Orleans." Dedication ceremonies were held on St. John's Day, June 24, 1923. St. John’s Day has a special significance for Masons—I've noticed it associated with other Masonic activities, over the years. For example, the excursion aboard the Barmore, on June 24, 1885, was under the auspices of the “Masonic fraternity” of Abbeville. In fact, this excursion is the one that we took together on another “Journey into the Past,” several years ago.

Despite inclement weather and poor road conditions—our parish, if not most of Louisiana, still had unpaved highways—representatives from many lodges drove to Abbeville to partake in the dedication ceremonies. The names of many of these visitors were reported by the Abbeville Progress. It also listed the names of at least 75 local Masons who had registered that day, as well as the names of the others who were not in attendance. I will note only the names of Abbeville’s officers. They were J. H. Williams, F. C. Stebbins, Abbot J. Hayes, H. A. Broussard, W. S. Hayes, S. O. Olivier, W. W. Durke, Lloyd B. Miller, M. M. Fletcher, W. W. Montagne, Harry Schriefer, and Max Harrel.

Following a session of the Grand Lodge at the courthouse, the dedication ceremonies were then held at our new temple.

J. H. Williams, according to the Abbeville Progress, as “Master of Abbeville Lodge, presented the building to the Grand Lodge for dedication.” The “working tools,” according to “Masonic tradition,” were used in these rites. They were: (1) “a vessel of corn” which was used to dedicate the temple to “usefulness,” (2) a vessel of wine which was used to dedicate it to “virtue,” and (3) a vessel of oil which was used to dedicate the temple to the “universal benevolence.” These dedication activities, which were open to the public, were performed inside the temple. Following these rites, everyone then returned to the courthouse for yet another speech.

Throughout this glorious day, the Masons, their families, and their friends consumed “delicious refreshments and good eats that were served on the lower floor of the Temple,” according to the Progress. It credited the food and refreshments to the “ladies of the Eastern Star and the wives of the members of the Masonic Lodge.” I’ve noticed in this instance and in others that it was a good thing that Abbeville had more than one newspaper during those years. While the Progress gave the dedication of the Masonic Temple major coverage, the Meridional hardly reported on it at all. Naturally, the reverse, in extent of coverage, had been the case in other situations.

This building continues to serve the Masons as well as the public. At one time it was used by the community as our library. When the current courthouse was constructed, this Masonic Temple was turned into a temporary courthouse, as had been the previous Hall. It housed the offices of the clerk of court, the sheriff, and the assessor, from January 1951 until February 1953.

Well, we've visited the buildings that we know were designed by C. G. Honold. From them we get some sense of the man. We can learn more about him and his social status by looking at some of the activities in which he participated, and by meeting some of the individuals with whom he associated. Regrettably, I probably failed to copy some of the social events in which Honold took part.

Honold lived with his sister, Miss Eugenie Honold. In general, I did not copy items related to her as I went through the newspapers. However, I did note that on August 27, 1913, Miss Honold was the secretary pro tem for the Woman Suffrage meeting at the courthouse. In October 1914, she was listed as the secretary and treasurer of the local Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.

One night in early December 1902, George attended a dance at the Opera House, also known as the French Hall. Others in attendance included these gentlemen: A. J. Thomas, Jonas and Jake Weill, Dr. J. Kibbe, Charles Corrodi, Joe Lyons, John Shaw, and Professor Pate. The Misses at this dance included Myrtle Sokoloski, Maud Stebbins, Rosa White, Minnie Putnam, Heloise Degeneres, Gussie and Laura Summers, and Sadie Fritz. Some of the married women who were there without their husbands were Mrs. E. M. Stebbins, Mrs. L. J. Feray, Mrs. A. J. Godard, and Mrs. Percy Summers. Also present were Mr. & Mrs. Frank A. Godchaux [Sr.], Mr. & Mrs. R. J. Leguenec, and Mr. And Mrs. A. J. Golden.

In December 1906, Honold, along with Augustin Morton, Columbus Trahan, Paul Leguenec, and Simon Gizardo traveled aboard the steamer Joe B. Chaffe to Bayou Chene. There the remains of Jack Kibbe—Morton’s brother-in-law—were carried on board the steamboat and were transported to Abbeville.

In October 1907, Honold and J. R. Leguenec went hunting and “bagged quite a few birds.” Early in January 1909, Honold “treated some of his friends to a launch ride on the Bayou.”

Honold went to the "seashore" for a few days with District Judge W. P. Edwards, W. B. Gordy, and Theodore Laporte, in March 1912. That September, Honold, Dr. R. P. Nelson, and Mayor Brasseux "motored" to Lafayette. I don't know whose car was used to travel over those unpaved, and probably ungraveled roads to Lafayette. In late September 1913, Honold took part in another “seashore party” with Judge W. P. Edwards, Sheriff Morton, P. J. Greene, and others. They traveled to “the bay and to Long Island by the 7th Ward Drainage Canal.” In January 1914, he traveled to the seashore with V. L. Caldwell, J. A. Summers, and W. B. Gordy.

In 1912, the town council selected Honold to supervise the "extensive cement sidewalk construction" that would cement blocks and blocks of sidewalks in Abbeville. This venture was completed in 1913. In connection with the sidewalk project, Honold, Mayor Adolph Brasseux, Alderman Dr. R. P. Nelson, and City Attorney Broussard drove to Opelousas, in January 1911, to inspect the sidewalks there. It was reported that after having inspected the sidewalks of other towns, this delegation chose the sidewalks of Opelousas as the "best sidewalks of all cities of the State of its size."

Another municipal enterprise in which George Honold became involved was the beautification of Magdalen Square. Mayor Adolph Brasseux and Frank Summers were also on the committee to oversee this project. They were selected in 1912. I presume that Honold supervised the day-to-day operations of both of these jobs and reported to the town council about the construction of the cement sidewalks, and to this special committee, regarding the beautification of the square. This latter project included the "planting of trees, and flowers, and to have the fountain fitted up with water plants and gold fish."

Now we come to the final chapter of George Honold’s life. Honold, as we’ve learned, died on Valentine’s Day in 1925. In 1921, he wrote his last will, leaving his estate to his sister, Eugenie. What worldly possessions did Abbeville’s premier architect have at the time of his death? Although not a rich man, he had $471 in the First National Bank and $1,106 in the Bank of Abbeville & Trust Co. Additionally, according to his succession, the Vermilion Parish School Board owed him $368. A shot gun was part of his estate. Had Honold used it on that 1907 hunt mentioned above? A “Ford auto” was part of his estate. Imagine him bouncing and rattling over our dirt streets and roads with their menacing potholes, like sand traps on a golf course.

His succession included “expenses of last illness.” They included a bill for $170 owed to Bourque and Brasseux, undertakers. Dr. E. Stanley Peterman was owed $25, and the “Funeral in New Orleans” cost $56.

For me, the most intriguing item in Honold’s estate was a drawing board. I would like to believe that many of the buildings that he designed—with a mixture of math, emotion, and aesthetics—were created on that board. Had it possibly survived the 1903 fire that destroyed the first Bank of Abbeville building and his office? It would be fantastic to have his drawing board on public display today!

Father Antoine Megret gave us the town of Abbeville, and E. I. Guegnon left us the Meridional, which continues to chronicle the life and times of Abbeville. Christian George Honold left us his magnificent, distinctive buildings that continue to enhance Abbeville’s cityscape.