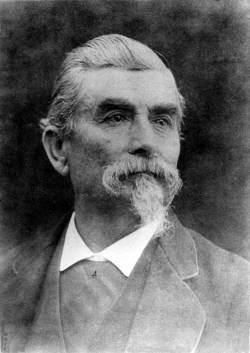

Jean-Pierre Gueydan

Jean-Pierre GueydanBy Patricia Saltzman Heard

[Click on footnote numbers to go back and forth between footnotes and text.]

History is a collection of facts and assumptions, which paint a story so that we may better understand who we are today. The historical events concerning Jean-Pierre Gueydan and the beginning of the town of Gueydan are based on facts in an attempt to tell the fullest and most accurate story possible. Documentation is provided for the viewer.

A short distance from the Mediterranean, on the southeastern coast in St. Bonnet, France, a young couple running a hotel would unknowingly contribute to American history. Pierre Gueydan and his wife, Victoire, purchased a hotel from her father, François Leauthier.[1] There, they reared three children: François, Jean-Pierre and Clara Gertrude.[2] Two of these children would venture across the ocean into pre-Civil War America and leave their name in a permanent location as a testament to their arrival.

François was the first who came to the United States on March 30, 1831,[3] and settled with his established and successful uncle, Jean or Joseph Leauthier, in New Orleans.[4] His uncle not only offered a home and further education, which was of the utmost importance to François’ father, but also a new opportunity. Whether he knew it or not, this opportunity would also offer a grand adventure. François would remain in the United States for fifty-four years and offer a supporting role in the establishment of a town in the southwestern section of Louisiana. Four years later his brother arrived to join them. It was November 30, 1848, and what a sight the busy southern port of New Orleans must have had on a nineteen year old boy named Jean-Pierre Gueydan.

The European culture from which Jean-Pierre came could not have been more different from the boisterous city of New Orleans, which was then the fourth largest city in the United States. A great deal of this pre-Civil War port city’s prosperity was based on cotton, which would later play a significant role in Jean-Pierre’s life. The city and the boy had a matching spirit. In future testimony,[5] Jean-Pierre described how he spent the years of 1849 through 1852 traveling up and down the Mississippi River. What an education he must have got—and how this must have influenced his future endeavors.

And so the adventure began. In 1852, after three years on the river, Jean-Pierre relocated to Abbeville, Louisiana, where he operated a business on Washington Street[6] for the next ten years. The year he arrived in Abbeville was also the year Miss Josephine Cecile Ducommun,[7] a 20-year-old Louisiana native, became his wife.[8] Before she died in 1860,[9] she gave him four children from their eight-year marriage: Leonce Pierre,[10] Elizabeth Alice, Victoire Emilie and Eugene Hippolyte Gueydan.

Leonce married Emma Guiseppe[11] before dying of pneumonia while on business in New York[12] while his wife and three children were living in Trinidad. Alice married a Frenchman, Joseph Chabassus, and lived the remainder of her life in France with her husband and four children.[13] Victoire Emilie died after living only ten days.[14] Eugene[15] married a native New Orleanean by the name of Amelie Marie Chanute[16] with whom he had three children. He spent a few years dividing his life[17] between his wife’s preferred residence in New Orleans and southwest Louisiana, which was the area he truly loved.[18] During that time he served as Gueydan’s first postmaster.[19] One of Eugene’s children is buried along with his sister Victoire Emilie and their mother Josephine in Abbeville, Louisiana.[20]

Meanwhile, in 1856 a business by the name of Gueydan and Company was operating as an “oil factory” in Abbeville. An old photograph from that era clearly shows the name F. Gueydan and Company – Studebaker Wagons advertised on a storefront. Whether these are the same business or whether François and Jean-Pierre had two separate establishments is unknown. We do know, however, that Jean-Pierre was also shipping cotton that he purchased and sold for growers in the area[21] on his boat, The Ingomar,[22] during this time. It’s conceivable that at least one of the brothers owned the store listed as an oil factory. Since there were no petroleum oil companies in Abbeville during that time, a good guess is that they may have been manufacturing cotton oil.[23]

Nevertheless, business for both brothers was soon interrupted. With the start of the American Civil War in 1861, cotton dealing became a risky venture. Jean-Pierre had been buying and selling cotton with Confederate money.[24] Shipping the cotton by river ran the risk of Union and possibly Confederate interference. Mr. Gueydan was no exception to the perils of war. He lost at least 157 bales of cotton that were marked with the initials PG, for which he would later ask restitution under the French-American Claims Commission Act.[25] During this time, he was also arrested by Col. Elijah Ewing of the Confederate Army for refusing to “go into the military service.”[26] He later returned to Abbeville, since a French citizen could not be forced to engage in fighting in an American war, but left again in 1862. With a country engaged in battle and wanting to put his troubles in Abbeville behind him, Jean-Pierre sold his store and invested in a cattle venture. With good credit[27] he acquired “420 head” of cattle from “a Texas party,”[28] which he planned to drive to New Orleans where François waited for him. The drive was to begin in Maurice, Louisiana, in August or September of 1862[29] near Camille Broussard’s plantation.[30] Five hired men accompanied Jean-Pierre on what would become an adventurous journey.

The plan was to follow Bayou Teche to New Orleans. They traveled east to New Iberia[31] hugging the bayou south to Tigerville, known today as Morgan City. Here they herded the cattle across a body of water and probably stayed west of present-day Lake Palourde and Lake Verret traveling on the east coast of the bayou, which took them on a more northerly route.

When they arrived at Bayou LaFourche, they decided to avoid Donaldsonville because they heard of skirmishing in that area.[32] That meant taking an even more northerly course. But bad luck would interfere and provide them with the skirmish they tried to avoid. When they reached Bayou Goula, Jean-Pierre Gueydan and Captain Sprague of the United States Army became formally introduced!

Placed under arrest for “guerilla” actions, Jean-Pierre immediately pulled out his French citizenship papers and proclaimed his innocence. He was held at the confederate prison, Camp Moore,[33] and sent to see General Butler. Meanwhile, the Union Army confiscated the entire herd of cattle and one of the driver’s horses. Another cattle driver managed to keep his horse by convincing the Union officer that it was too wild and hard to control. Jean-Pierre was escorted into New Orleans He arrived before dawn at Wilkins & Co. where he had prearranged for his cattle to be sold at $125 per head. He’d agreed to pay $45 per head for the cattle so he stood to make a handsome profit. Thanks to the Union Army, he was once again empty handed. François, who had been waiting for his brother, offered what help he could. They left for the customs house with a receipt intending to be paid for their losses.[34] However, the Union Army claimed that only 177 cattle had been taken and refused to pay the contracted price of $125. Jean-Pierre’s financial loss was of no concern to the Army but François satisfactorily brought the Colonial’s intention to profit from the seizure of the herd to light. The Colonial proceeded to argue over the reimbursement saying, “…but I am not allowed to pay you more than what they cost.” To which François replied, “…Yes, Colonel. You are going to pay my brother forty five dollars a head and you are going to charge the government one hundred and twenty five to one hundred and fifty a head.” The $45 compensation per head of cattle was all that Jean-Pierre would receive until 20 years later when, in 1883, the French-American Claims Commission would settle the matter.

None of these matters drained Jean-Pierre’s spirit nor undermined his determination. By 1863, he had a new lease on his future. He relocated to New Iberia where he opened a store[35] and married a New Iberia native, Amelie Azrael Montagne.[36] She was 29 years old. He was 34. In addition to the children from his first marriage, Jean-Pierre’s family grew by an additional five.

Marie Louise Henriette, called Louise, died young.[37] Amelie Victoire Arthemise,[38] called Amelie, married Alfred Amar in France and had one child. Henri Louis,[39] who eventually took over his father’s business proceedings, married three times after losing his first two wives to tuberculosis and childbirth.[40] Marguerite[41] married Louis Rauzier, of France, where they reared three children. The youngest sibling, Cecile Caroline[42] also married a Frenchman, George Fatou, and settled in Grenoble, France, to rear five children.

Three years later, in 1865, Jean-Pierre was settling a business dispute over cotton in a St. Martinville court. He argued that he purchased 50,000 lbs. of cottonseed from a Lafayette parish resident but had only received 6380 lbs. of the purchase. Cotton problems seemed his constant companion. In 1866, he was relieved of one of them when he sold the Ingomar to Pierre Rosier for $800.[43] He also left New Iberia for New Orleans where he, François, and Laurent Bodet opened a mercantile store called the Magasin Rouge near the present day French Market, which later moved near the customs house.[44] François left New Orleans four years later to spend the years 1870-1873 taking part in the Franco-Prussian War.[45] When he returned from France, the brothers decided to try their luck in Texas.[46]

The families moved to Corpus Christi then later relocated approximately 50 miles farther west to San Diego. Jean-Pierre owned goats and up to 15,000 head of sheep.[47] Besides the ranch, the brothers fell back on their experience as mercantile operators and opened another store, Gueydan Brothers & Co.[48] Both share credit in making advancements while living in Texas. Jean-Pierre invented an apparatus for shearing sheep[49] and machinery for making cactus edible by livestock while both of the brothers are given credit for introducing cotton farming to southeast Texas.[50]

While there, Jean-Pierre joined a company of Minute Men, not unlike the Home Guard that he joined while living in Abbeville during the Civil War. Family stories of their lives in Texas are recounted in a manuscript[51] left by Jean-Pierre’s daughter, Marguerite. The hardships they faced were sweetened by a happy and adventurous family life. While building a large sheep ranch was hard work, his financial standing must have improved for he planned to build a large house on his ranch he called the Santa Rosalia.

In 1882, while still living in Texas, he and François began land negotiations in the western section of Louisiana. The 19,000 acres described as worthless, unsettled marsh and prairie eventually earned Jean-Pierre the reputation of a man who must have lost his mind while living in Texas. In 1883, the French-American Claims Commission settled two separate claims that both Jean-Pierre and François filed.[52] They testified as to their property losses and were compensated and awarded $20,000 plus 5% interest amounting to a grand total of $41,000.[53] The brothers had previously entered into a secret, legal agreement with one another in which they promised to fight the American government, use part of the earnings to honor their previous cotton and cattle debts as best they could and divide the proceeds by an agreed upon amount.[54] With their claims now settled, both men decided on their futures. In 1883, they sold their Texas property and dissolved Gueydan Brothers & Co. which netted Jean-Pierre $90,000.[55] With these monies and the settlement from the French-American Claims Commission, the brothers headed to Louisiana to purchase the land that Jean-Pierre began negotiating on the previous year. In addition to this large tract of land, the brothers also owned 680.20 acres of land where the town of Gueydan is presently located.[56]

By 1885, François, now 67 years old, decided to retire. He liquidated his holdings, with Jean-Pierre as the buyer and returned with his family to France. François’ partial earnings were allotted to $8140.20 or approximately $24 per acre for the 680.20 acres where the boys set up their homes.[57] His sister, Clara Gertrude, welcomed her brother home and helped him resettle in Grenoble.[58] Although his brother and lifelong business partner was gone, Jean-Pierre remained in America where his most well known legacy was about to begin.

He fenced 30,000 acres, which he rented for pasture. In 1887, he advertised for business in the Abbeville Meridional and also warned that trespassing was forbidden. If the closure of this formerly open land angered those in the area, it wasn’t the first time Jean-Pierre faced local wrath. He’d had such troubles while in Texas. But, he’d also made the acquaintance of several Texans and managed to lure seven families from Seguine, a town in Guadeloupe County, to settle in southwest Louisiana. As this was taking place, Jean-Pierre decided to switch ventures and try his hand at raising rice. Most of his acreage was of low elevation with a high water table. More importantly, the natural clay pan below the surface helped to hold the water necessary for growing rice. With a little help from nature, Gueydan was on its way to becoming a major rice producing area. In the vast amount of properties that he owned, Jean-Pierre sectioned off some for his own use while selling off other sections. He kept the parcel south of the town of Gueydan for his home establishment and named the site St. Bonnet Plantation.[59] He also chose a section in order to develop a community he called Gueydanburg.[60]

In 1888 his son, Henri, was managing most of the daily business affairs. At 63 years old, Jean-Pierre left for France in 1892 for an extended visit with his wife and daughters. Their intention was to give the girls enough time to find suitable French husbands. He returned two years later obviously in a comfortable financial position.

Now back in Louisiana, Jean-Pierre was fully engaged in rice production. Having realized the value of an irrigation system to ensure water availability for crops, he gathered with Gueydanburg members named Daspit, Garland, and Levert to form the Vermilion Development Company. This group would later become known as the Vermilion Irrigation Canal Company and, finally, the Acadiana-Vermilion Rice Irrigation Company. The company’s initials can be seen on the concrete bridges surrounding the town of Gueydan, which cross the system of drainage canals the company developed.[61] Knowing the importance that his father placed on education, Jean-Pierre provided a way for the children of the community to receive the same.[62] Education began in a one room building on St. Bonnet Plantation from local lumber sawed at Evans’ sawmill on Bayou Queue de Tortue. Nine children were ready to begin but the school was one pupil short of obtaining a teacher. A neighboring child was found and the first school was underway. Along with a growing community came families and soon the school population outgrew the small building. The building was enlarged twice before a new school was built in the fledgling community on land donated by Jean-Pierre.[63]

1895 saw major changes in the community while registering a personal defeat for Jean-Pierre. The death of his oldest son, Leonce, was the third time he would lose one of his children. However, he continued to push for progress in the settlement. A contract was drawn with William W. Duson and Cornelius C. Duson to plan the foundation for a formal town.

The name, Gueydanburg, was also changed to Lockwood and the Duson brothers were to receive half of the value of the land as their fee.[64] Jean-Pierre had also managed to lure the Southern Pacific Railroad to the area by donating land to lay tracks. This path would take the railroad eleven miles farther south than its Midland, Louisiana, location and would allow the shipment of rice by train rather than water. Faster shipment was a sound business decision.

An improved irrigation system could help to boost land sales. Jean-Pierre’s acquaintance with C. L. Shaw[65] of the Southern Pacific may have been the key to this development. Upon Mr. Shaw’s suggestion to use the canal system to irrigate the rice fields, Jean-Pierre developed a pumping plant, installed at Primeaux’s Landing[66] north of the town of Gueydan.

“A Mr. Gueydan of Vermilion built the largest plant in the world for flooding rice in 1895. This plant was guaranteed to supply 50,000 gallons of water per minute on a fourteen-foot lift. When tested it actually threw 60,000 gallons twenty feet high! The plant was built to supply water to 14,000 or 15,000 acres of rice. Gueydan planned to rent sections of land to farmers which would be supplied with water from the canal. Many farmers eagerly moved that they might be assured of water for their rice crops at the right time.”[67]

National advertising to market the “Holland of America” was designed to draw farmers into the area. A turn of the century brochure stated,

“We have the lands and want good land owners on them. Come early and avoid the rush. Why live in the cold north, when you can come south … we will do anything to please you, except give you the lands. – Gueydan & Babbit”[68]

It was now Henri Gueydan’s turn to take over the reigns and his was the Gueydan name referred to in Gueydan & Babbit. The town was progressing and Henri would remain behind while Jean-Pierre once again returned to France for an extended visit. Henri’s brother, Eugene, also remained behind with Henri.

In 1896, Jean-Pierre bought back all rights to the lands sold to the Duson brothers for $3000[69] and the name of the town was changed from Lockwood to Gueydan.[70] Lot sales began!

On July 19, 1899, Governor Murphy Foster signed the document officially proclaiming Gueydan as a “village.”[71] One year later, Jean-Pierre Gueydan died in Marseille, France, on November 20, 1900, while waiting for passage to return to the United States.[72] In 1902, Governor William Wright Heard signed the proclamation granting Gueydan status as a town.[73]

Through all of his trials, Jean-Pierre lived long enough to see his dream of settling this land become reality. The “worthless lands” that he purchased are now considered prime hunting and farming properties. The town of Gueydan is located on a major north-south flyway and during the early part of the 20th century it was not unusual for the sky to be blackened by the number of waterfowl leaving the marshlands. The farmland in cultivation today is a boundless sea of green, followed by gold in the fall, stretching to a point where the horizon becomes almost invisible.

While settled by a Frenchman who never became an American citizen,[74] the town of Gueydan and surrounding area’s population today is descended from not only the French but also the Midwesterners of largely European nationalities and the north Louisianans who came to settle and farm the area. We are today the effect of a spirited and visionary man. To quote a local historian, “His slide down life’s slopes here in Louisiana and in Texas had to have been more challenging and exhilarating than skiing down any slope the Alps could have provided. Mr. Gueydan made the right choice for himself and for Vermilion Parish.”[75]

While it is often written that Jean-Pierre Gueydan became an American citizen in his old age and was buried in the family tomb in St. Bonnet, neither of these can be proven true. In fact, no paperwork proving American citizenship can be found and his French family maintains that he never became a formalized American. At some point, his burial location was changed. This locality was once known by family but was unrecorded and there are no family members living today or local church or government officials from St. Bonnet who can confirm the location.

Patricia Saltzman Heard

FOOTNOTES

[1] Letter from Olivier Gueydan, Descendant of François Gueydan, Tour-de-Peilz, Switzerland, February 20, 1999, to this writer.

[2] Family Birth Certificates, Olivier Gueydan, February 20, 1999 to this writer.

[3] Letter from François Gueydan to his father, Pierre “Panice” Gueydan, New Orleans, November 28, 1844. He was thirteen years old upon his arrival.

[4] Letter from Loic Jacques Barral, descendant of Jean-Pierre Gueydan, Vernon, France June 1999, to this writer.

[5] “French-American Claims Commission,” House Executive Documents, 2nd Session, 48th Congress, 1884-1885, vol. 30 (Serial No. 2305), Claim No. 226, Testimony of Jean Pierre Gueydan taken between 1881-1883.

[6] Dupuy, Ken, “Jean Pierre Gueydan,” Abbeville Meridional, three weekly installments beginning January 30, 1996.

[7] Gueydan Family Records, Josephine Cecile Ducommun, born 1832.

[8] Gueydan Family Records, Jean-Pierre Gueydan married Josephine Ducommun, August 24, 1852.

[9] Burial of Josephine Cecile Ducommun, Old Catholic Cemetery, Père Mégret Street, Abbeville, Vermilion Parish, La., b. 1832, d. October 6, 1860.

[10] New York Times, Leonce Gueydan, born 1853, Abbeville, Louisiana.

[11] Gueydan Family Records, Emma Guiseppe, born 1860, Port-of-Spain, Trinidad. It is not officially known when or where Leonce Gueydan and Emma Guiseppe were married although it was probably Port-of-Spain, Trinidad, where he was living and working at the time.

[12] Succession of Jean-Pierre Gueydan, dated February 4, 1901, Succ. #425, Vermilion Parish Courthouse, Abbeville, La., Leonce Pierre Gueydan, d. Feb. 27, 1895, New York, NY. Also, New York Times obituary pasted to a photograph of Leonce Gueydan from the family files of Leslie Lynn Beasley Riley, descendant of Jean-Pierre Gueydan, to this writer.

[13] Gueydan Family Records, Alice Gueydan, born 1855. The year of Alice Gueydan’s death and marriage is unknown. Any other information on Joseph Chabassus is also unknown.

[14] Burial of Victoire Emilie Gueydan, Tombstone, Old Catholic Cemetery, Père Mégret Street, Abbeville, Vermilion Parish, La., b. March 2, 1857, d. March 11, 1857.

[15] Gueydan Family Records, Eugene Gueydan, b. March 26, 1858, d. June 22, 1928.

[16] Eugene H. Gueydan married Marie L. Chanute, October 27, 1885, Murray, Nicholas Russell, Computer Indexed Marriage Records, Orleans Parish, Louisiana 1830-1900, Hammond, Louisiana, Hunting For Bears, p. 779.

[17] Burial of Eugene Hippolyte Gueydan, New Orleans Cemetery, Gueydan Family Plot, Esplanade Street, New Orleans, La.

[18] Letter from Marie Gueydan Hester, Tallulah, Louisiana, to Roland Gueydan de Roussel, Le Vesinet, France, October 26, 1969.

[19] Letter from Marie Gueydan Hester, Tallulah, Louisiana, to Roland Gueydan de Roussel, Le Vesinet, France, October 26, 1969. Appointed first postmaster on May 27, 1896, Dupuy, Ken, Abbeville Meridional.

[20] Discrepancy in two records: Southwest Louisiana Records – Church & Civil Records, Rev. Donald J. Hebert, vol. 23, 1892, c. 1980, GUEYDAN, Marie Emilie Octavie, d. 11 Aug. 1892 at age 2 mths. 9 days, (Abbeville Ch.: v. 3, p. 18). Old Catholic Cemetery, Père Mégret Street, Abbeville, La, tombstone cites death August 10, 1892.

[21] French-American Claims Commission, Claim No. 226, Testimony of Jean Pierre Gueydan.

[22] Dupuy, Ken, “Jean Pierre Gueydan.”

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

[25] French-American Claims Commission, Claim No. 226, Testimony of Jean Pierre Gueydan.

[26] Dupuy, Ken, “Jean Pierre Gueydan.”

[27] Gueydan Family Files, Legal Agreement Between Jean-Pierre and François Gueydan, Filed Oct 25, 1901, Simonet LeBlanc, Abbeville, La.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Department of the Interior, Pat. WA 77428, Vol. 470, p. 184, order no. 317680-S, in a letter from Ken Dupuy to this writer, Camille Broussard’s 161 acre Plantation, now a large part of the town of Maurice, situated on the east side of Hwy. 167, coordinates: SW ¼ of Section 12 Township 11 S of Range 3 E, was land he obtained in an 1855 land grant from the United States of America.

[31] French-American Claims Commission, Claim No. 226, Testimony of Evaniste Trahan.

[32] French-American Claims Commission, Claim No. 226, Testimony of Venance Trahan.

[33] Dupuy, Ken, “Jean Pierre Gueydan.”

[34] For historical purposes, that receipt mentioned was reported burned in a fire in New Iberia. French-American Claims Commission, Claim No. 226, Testimony of Jean Pierre Gueydan.

[35] Dupuy, Ken, “Jean Pierre Gueydan.”

[36] Hebert, Rev. Donald J. Southwest Louisiana Records – Church and Civil Records, vol. 7, (1861-1865), c. 1977, GUEYDAN, Jean Pierre (Pierre & Victoire LEANTHIER [sic]), m. 12 Dec. 1863, Amelie A. MONTAGNE (NI Ch: v. 1, p. 263).

[37] Hebert, Rev. Donald J., Southwest Louisiana Records, vol. 7, c. 1977, GUEYDAN, Marie Louise (Pierre & Marie Amelie MONTAGNE) b. 14 Oct. 1864 (NI Ch.: v. 1, p. 308).

[38] Gueydan Family Records, b. about 1866, died May 5, 1937, France.

[39] Birth and Death of Henri Louis Gueydan: b. Dec. 22 1867, Congo Square, New Orleans, La., d. April 26, 1952: Interred Washing D.C. Conrad, Glenn R., Ed., A Dictionary of Louisiana Biography, vol. I, A to M. Lafayette, La., c. 1988, p. 364. (Note: several sources verify birth and death.)

[40] Burial location of Amalia Arroyo Gueydan, Gueydan Cemetery, Gueydan, Vermilion Parish, La., next to her son Henry Pierre Gueydan. Both died of tuberculosis. Mercedes Alvarado Gueydan died of childbirth. These sources from Mercedes Hester Eichholz, Santa Barbara, California, April 1999.

[41] Unknown when Marguerite Gueydan was born, married Louis Rauzier or died.

[42] Gueydan Family Records, Cecile Caroline Gueydan, b. July 28, 1875, Corpus Christi, Tx., d. March 3, 1944, France.

[43] Dupuy, Ken, “Jean Pierre Gueydan.”

[44] Notes from George Fatou, France, descendant of Jean-Pierre Gueydan, compiled with information from Henri Louis Gueydan and the Gueydan Harvest Times, August 21, 1979.

[45] Letter from Roland Gueydan de Roussel, Le Vesinet, France, to Marie Gueydan Hester, Tallulah, La., October 16, 1969.

[46] Notes from George Fatou, August 21, 1979.

[47] Fortier, Alcée, Lit. D., Editor, Louisiana: Comprising Sketches of Parishes, Towns, Events, Institutions, and Persons, Arranged in Cyclopedic Form (vol. 3), Century Historical Association, c. 1914, pgs. 526-529.

[48] Notes from George Fatou, August 21, 1979.

[49] Ibid.

[50] Fortier, Louisiana: … pgs. 526-529.

[51] Gueydan, Marguerite, translated into English by Alain Barral, Helene Carbonel and Loic Barral, Retrospective Paintings of By-Gone Days In Texas, November 2000.

[52] French-American Claims Commission, Claim No. 226 filed for Jean-Pierre Gueydan, Claim No. 181 filed for François Gueydan, testimony from 1881-1883.

[53] Succession of Jean-Pierre Gueydan, Succ. #425, Vermilion Parish Courthouse, Abbeville, La.

[54] Ibid.

[55] Dupuy, Ken, “Jean Pierre Gueydan.”

[56] State of Louisiana to François and Jean-Pierre Gueydan, Patent 4990, Signed Governor S. D. McEnery, Patent Bk., v. 21, p. 270, June 18, 1867, Conveyance Bk., v. 4, p. 2, entry 1852, Clerk of Court’s Office, Vermilion Parish Courthouse, Abbeville, La.

[57] François Gueydan to Jean-Pierre Gueydan, Cash Warranty Deed, June 5, 1885, recorded June 25, 1885, Conveyance Bk., v. 1, p. 311, entry 229, Clerk of Court's Office, Vermilion Parish Courthouse, Abbeville, La.

[58] Gueydan Family Files.

[59] Succession of Jean-Pierre Gueydan, Succ. #425, Vermilion Parish Courthouse, Abbeville, La.

[60] Abbeville Meridional, 1889.

[61] Saltzman, Lucille Marie, A Study and Survey of Community Resources of Gueydan, Louisiana, that can be used to Enrich The Elementary Social Studies Curriculum, Thesis (MA), Baton Rouge, La., LSU, August 1941, 108 pgs. Ill., diagrs.

[62] Ibid.

[63] Notes from George Fatou, August 21, 1979.

[64] Agreement, Power of Attorney and Conveyance, June 8, 1895, Jean-Pierre Gueydan to William W. Duson & Cornelius C. Duson, recorded December 21, 1895, Conveyance Bk., v. 13, p. 708, entry 7344, Clerk of Court’s Office, Vermilion Parish Courthouse, Abbeville, La.

[65] “A History of Rice Production in Louisiana,” Louisiana Historical Quarterly, v. 23, Jan. – Oct. 1940, pgs. 568-569, Louisiana Historical Society, New Orleans, La.

[66] Saltzman, Thesis, August 1941.

[67] “A History of Rice Production in Louisiana,” Louisiana Historical Quarterly, v. 23, Jan. – Oct. 1940, pgs. 568-569, Louisiana Historical Society, New Orleans, La.

[68] “A Twelve Thousand Acre Proposition in the Holland of America,” circa 1910 brochure, Personal Files of Mercedes Hester Eichholz, Santa Barbara, California, 2000.

[69] Retrocession, November 17, 1896, William W. Duson & Cornelius C. Duson to Jean-Pierre Gueydan, recorded November 21, 1896, Conveyance Bk., v. 15, p. 270, entry 8049, Clerk of Courts Office, Vermilion Parish Courthouse, Abbeville, La.

[70] Change of Name of Townsite, November 16, 1896, Lockwood to Gueydan, recorded November 21, 1896, Conveyance Bk., vol. 15, folio 274, entry 8050, Clerk of Court's Office, Vermilion Parish Courthouse, Abbeville, La.

[71] Proclamation, July 19, 1899, Signed by Governor Murphy J. Foster, Charter Folder for the Town of Gueydan, 19th Floor, Office of the Secretary of State, Louisiana State Capital, Baton Rouge, La.

[72] Conrad, Glen R., A Dictionary of Louisiana Biography, v. I, A-M, published by The Louisiana Historical Association in cooperation with The Center for Louisiana Studies of the University of Southwestern La.

[73] Proclamation, December 23, 1902, Signed by Governor William Wright Heard, Charter Folder for the Town of Gueydan, 19th Floor, Office of the Secretary of State, Louisiana State Capital, Baton Rouge, La.

[74] Gueydan Family Files, 1999.

[75] Dupuy, Ken, “Jean Pierre Gueydan.”