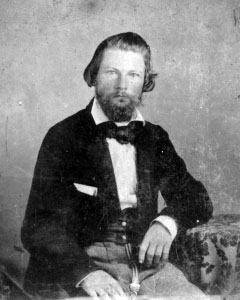

Photo courtesy Mrs. Mae Dee Landry

E.

I. Guégnon

E.

I. Guégnonby Kenneth A. Dupuy

Guégnon is more than the name of a street in Abbeville. It is a family name, the name of Eugène Isidore Guégnon, the founder of The Meridional, one of the oldest newspapers in Louisiana at this time.

E. I. Guégnon, as his name usually appeared in print, was a native of France. He was born in 1819, to Nicolas Guégnon and Marguerite Tabouray. By 1837, he was in the Attakapas area. That is the year that Eugène Isidore Addison was born to Mr. and Mrs. George Addison in Opelousas. I assume that E. I. Addison, who also figures prominently in Abbeville's history, was named after E. I. Guégnon. Guégnon and George Addison were partners at this time as publishers of the Opelousas Gazette. By 1840, E. I. Guégnon had moved to St. Martinville.

Before picking up Guégnon's story in that town, let me tell you more about George Addison. His was one of the first newspapers in Opelousas. When Guégnon separated from the Opelousas Gazette, Joel H. Sandoz joined Addison. They conducted business as Addison & Sandoz until Geo. Addison’s death in 1852. Some of the items listed in Addison's estate were the usual printing items as well as several slaves, and a "bowie knife!" This last item sounds so intriguing to me, probably because it and its inventor have become things that legends are made of. It is as though the words "bowie knife" are whispered in my mind, like some mystical object. I wonder whatever happened to George Addison's knife. Following Addison's death, Sandoz began publishing the Opelousas Courier, from which I was able to find some information about Abbeville. We will return later to George Addison's succession sale.

In 1840, E. I. Guégnon had moved to St. Martinville. On September 23, he purchased a printing press, type, and other printing materials in New Orleans. For less than a year, he published the Creole in St. Martinville. His printing shop was in a house owned by Jean Baptiste Derbes.

Guégnon was sued on April 24, 1841 for payment of the note ($557) with which he had obtained his printing materials. Three days later, he accepted three notes amounting to $1,500 and sold the Creole to Andre Meynier of New Orleans. Fourteen years later, Guégnon received final payment of those notes.

Only a few days after selling the Creole, on May 6, 1841, Guégnon married Valerie Neveu, widow of Alexander Bailey, and mother of Judge Adolph Bailey. Valerie was the daughter of Jean Jacques Neveu and Marguerite Rosalie Lefort. All three emigrated from France. Valerie was born in 1808 at Rouen, and she was only four years old when she and her family arrived in New Orleans. Valerie, according to her obituary, "mastered the English and French languages and she was a good Latin scholar." She married William A. Bailey of Henry County Virginia, in 1830, in Vermilionville. By 1834, Bailey’s succession had been recorded in the courthouse.

At the time of her marriage to Guégnon, she was a relatively wealthy woman. Some of the property that she brought into this marriage included 325 acres of land, two town lots in Vermilionville on Vermilion Street, 15 head of cattle, some furniture and three slaves. Sadly, owning slaves was a common practice at that time in our history.

The Guégnon marriage produced three children: Marie Mathilde, Marie Eugenie, and Eugène. We will meet these individuals later.

Apparently, Guégnon lived in Vermilionville. In February 1842, he had begun to publish the Impartial, a newspaper that was used later by governmental bodies in Vermilion Parish to publish their official proceedings, since there weren’t any newspapers in that parish until 1847. He continued publishing this journal until about 1853.

In April 1842, Guégnon entered into a contract with Daniel O'Bryan, Charles Mouton, Andre Martin, Antoine E. Mouton, and Edmond Mouton. Guégnon agreed to support, in the Impartial, Alexandre Mouton's bid for the office of governor. In exchange for his backing Mouton, the other individuals in the contract furnished a list of 103 names or subscribers to his newspaper from the towns of Vermilionville, Pont Breaux, Pont Perry, and St. Martinville.

In 1845, Guégnon went to court claiming that these men had promised to ensure the 103 subscriptions for Mouton's term as governor. He claimed further that these men should pay for the subscriptions out of their own pockets, and said that they owed him $2,472. The other parties to the contract said that the agreement was only for the time of the campaign, that subscribers had paid, and that Guégnon had not always ensured that the subscribers received their papers.

In 1846, the defendants were ordered to pay Guégnon $60.30. He may have gone to the Louisiana Supreme Court, but I don't not know the outcome. I thought it interesting that Guégnon was influential in getting one of our most famous governors elected, and also that his Impartial was circulated so widely. Also, Daniel O'Bryan had fought to get the seat of justice for Vermilion Parish established in Pont Perry; he was the son-in-law of Robert Perry, Pont Perry's founder.

In 1842, when Guégnon began publishing the Impartial, Father Antoine Mégret arrived in Vermilionville to become the new pastor at St. John's. These two individuals met under unpleasant circumstances. The church wardens resented and resisted Father Mégret's attempt to gain control of their church. After all, this power had been given to them by the state legislature; also, Mégret was a foreigner. While in France, Mégret had actively protested against government control of the churches, and now in Louisiana he was confronted with citizen control of the churches.

The battle lines were drawn, and E. I. Guégnon backed the church wardens. By March 1843, according to Mégret, Guégnon had written against him and the bishop for six months! Again, on August 2, 1843, just days after he had bought the future site of Abbeville, Father Mégret complained about Guégnon's continued attacks against him in the Impartial.

Six months later, Mégret wrote about a favorable change in Guégnon. After several conversations, Guégnon proved to be worthy of Mégret's confidence. Can we say that Mégret turned Guégnon's attitude around? Whether or not this is correct, we know that Mégret won over the church wardens, who in 1846 relinquished control of St. John's church to Father Mégret and to the Catholic Church.

By 1846, E. I. Guégnon had become a deputy clerk of court in Lafayette Parish; in 1849 he still held this position. During that time, he continued to publish the Impartial, which carried the proceedings of the Vermilion Parish Police Jury. Neither Abbeville nor Pont Perry had its own newspaper until 1847, and the Impartial was probably Vermilionville's only newspaper.

Guégnon took the office of Clerk of Court of Lafayette Parish in 1850 and seems to have held it until 1853. During this three-year term, Guégnon frequented a "coffee house" on Main Street in Vermilionville where he ran up a tab of $255 for "liquor drunk at the bar" and for "games of Billiard." Billiard games cost 20 cents each, while a glass of liquor cost 5 cents. Prices have sure changed since then.

In 1852, George Addison, Guégnon's friend (relative?), died leaving several minor children. In 1853, Guégnon became "tutor" to E. I. Addison, and to Addison’s sister Augustine. She lived with them a short time until she married. At George Addison's succession sale in 1853, Guégnon bought a printing press, a job press and other printing material, including a "keg of ink." While larger quantities of ink are purchased by newspapers today, surely it isn't packaged in a keg.

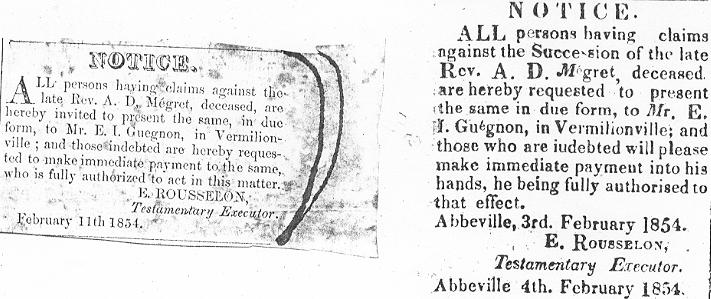

Upon Father Mégret's death in December 1853, Guégnon became the individual whom those having claims against Mégret's succession, and those who were indebted to the succession, were to contact. Isn't it ironic that a man who had attacked Mégret repeatedly in his newspaper ten years earlier, was now handling his succession. What may be even more ironic is the fact that Guégnon sold the Impartial to Father Mégret and Emile Veazey only days before Mégret died in the yellow fever epidemic! The newspaper remained in Mégret's succession until it was ordered to be sold by Sheriff Voorhies in 1858. It was still being published in 1854 [see below]. Was Guégnon still at the helm?

At Mégret's succession sale, held in Abbeville in November 1854, Mrs. Guégnon was adjudicated 60 arpents of land next to the town of Abbeville for $400. In the previous month, she had sued to be separated in property from her husband. Mrs. Guégnon claimed that her husband had received considerable sums of money from the sale of some of her property, and that he had received over $900 from persons indebted to her before her marriage.

Separation and control of her property were eventually granted to Mrs. Guégnon in October 1856. In partial payment of money owed to his wife, Guégnon sold and transferred to her, on December 19, 1856, "One certain printing establishment with all its contents, and heretofore known as the Independent of Abbeville...but now used and to be hereafter used for the publication of the Meridional in Abbeville." This company was assessed at $900. Therefore, the Meridional was being published in Abbeville sometime prior to December 19, 1856.

Also included in this particular settlement, Guégnon transferred to his wife three promissory notes (totaling $900) drawn by Emile Veazey and Father A. D. Mégret on December 1, 1853, just two days before Mégret died. These notes must have been for payment for the Impartial. The lives of Father Mégret and E. I. Guégnon touched several times. Examples of the two newspapers’ print are to be see in this photo. The one on the left was from the Impartial, while the one on the right was from the Independent. It is probable that the first issues of the Meridional were printed with this same lot of type.

In the 1860 census, Guégnon is listed as an editor. In 1891, there is a reference to his having been a justice of the peace. I found no evidence that he was ever a judge, as tradition has it. Perhaps his holding office as a justice of the peace may have led to this assumption, in that today some such office holders are referred to as "judge." Guégnon seems to have published the Meridional until his death in 1862.

According to Father Hebert’s volumes, E. I. Guégnon’s son, Eugène, was born on July 25, 1843: the very day that Father Mégret purchased the future site of Abbeville. Eugène took over the publication of the Meridional, following his father’s death. He was excused from military service during the Civil War because of the fact that he was a justice of the peace. On October 30, 1865, he married Ursule Blanchet, daughter of Clairville Blanchet and Caroline Boudreaux. The marriage took place in Abbeville. They did not have any children, as far as I could determine, so the Guégnon family name disappeared from this area when Eugène Guégnon died in 1877; his wife died the following year. Eugène was elected secretary of the town council on May 27, 1866 and continued in that capacity for a couple of years. The 1870 census states that he was a Parish Judge. Perhaps that is where the mistake was made that his father had been a judge.

It is interesting to note here that the first volume of the minutes of Abbeville's town council was used initially for something other than as a record of this governmental body's proceedings. Indeed, the first 32 pages of this ledger are a record of the accounts owed to the Meridional!

Some interesting facts can be gleaned from these accounts. For example, Mayor James K. Belden was charged $15 "for printing bills to the amount of $300." This item seemed cryptic to me, until I realized that Mayor Belden's signature appears on a 25 cent confederate "bill" that Mr. Randy K. Haynie, a Lafayette businessman, has in his collection of currencies. So, here in 1863—in the middle of the Civil War—the corporation of Abbeville was having Confederate currency—most probably in small denominations, like the 25 cent bill now in Mr. Haynie's collection—printed by the Meridional.

These accounts also reveal that A. Berard was sheriff in 1865 and 1866. This fact refutes a 1944 newspaper article that listed the sheriffs of Vermilion parish. That article stated that Alexandre Lege, Sr. had been sheriff from 1858 until 1868.

The next entry, following the records of the Meridional accounts, is an entering of the 1850 incorporation of the town of Abbeville. It was transcribed by E. Guégnon, who was "Secretary of the City Council of Abbeville." This copy of the incorporation was dated April 30, 1867. The next entry is the minutes of the town council that were taken on October 13, 1865; they were not transcribed in this journal until April 30, 1867. I wonder what became of the minutes of Abbeville's town council from at least 1850, until these minutes were entered? Also, I wonder why these minutes weren't put in this record book until almost two years after they were recorded. Had Eugène Guégnon not been the secretary of the town council, it is unlikely the Meridional's ledger would have been used as the first record book of the town council's minutes.

Several years have passed since we originally took this journey to meet the Guégnons. I have since solved the mystery regarding the minutes of the town council. Eugène, secretary of the town council, didn't record the town council minutes in the volume that has become Volume 1, initially. I don't know where his original minutes were kept. However, on February 6, 1867, the council authorized payment of $15 to Eugène to purchase a "Record Book." It was shortly thereafter, as secretary of the council, that he began transcribing the minutes into the book originally used as the Meridional's ledger. Had he kept the money and started using that ledger shortly after he was authorized to purchase a record book? Whatever the case may be, this ledger and a blurb in the newspaper explain why the minutes of the town council begin in 1865, and not in 1850 when Abbeville was incorporated. The Meridional noted that at the time of the destruction of the courthouse by fire—April 7, 1885—the then current record books of the town council and of the school board had been in the hands of the secretaries of these governmental bodies. Indeed, looking at Volume 1 of the town council minutes, one finds that the minutes begin in 1865 and continue until 1892. The previous minutes were destroyed when fire destroyed the courthouse, where the town council had been meeting, by at least shortly after the Civil War. Apparently, the school board was also housed in the courthouse, and that is why its surviving minutes start in 1876, and not earlier.

E. I. Guégnon has numerous descendants, even though the Guégnon family name is not to be found in this area today. His daughter, Marie Eugenie, was born on February 27, 1842, in Vermilionville. She married Dr. Henry O. Read, who, by 1859, was practicing medicine in Abbeville, and who was also the mayor that year. He was elected mayor again in 1866. In 1869, he was an alderman here in Abbeville. For a short while, perhaps a year, Dr. Henry O. Read served with the Confederate forces as a surgeon. Dr. Read and Dr. W. D. White were partners during the yellow fever epidemic of 1867 which took the lives of some Abbevillians.

Eugenie and Dr. Read, who were married on May 21, 1860, had four sons, three of whom became physicians, while the other became a minister. Their daughter, Valerie Elizabeth Read, died at age 5, in 1870.

Mr. & Mrs. E. I. Guégnon's other daughter, Marie Mathilde, married Dr. Francis D. Young, the son of Notley Young, a pioneer settler of Vermilion Parish. They were married on October 9, 1862. Dr. Young practiced in Abbeville from the 1850s until 1887. He and Mathilde had several sons, all of whom became physicians. Their daughter Kate married Dr. Clarence J. Edwards. Many of the individuals named in the last two paragraphs will be subjects of upcoming visits in the past.

Now that we’ve met Eugène Isidore Guégnon and his family, may you think of more than a street name the next time you see or hear the name "Guégnon."

Kenneth A. Dupuy